Currently there is a lot of focus by financial markets on the rate of inflation and whether the recent increases in the UK inflation reading will be temporary or more permanent.

Over the last 10 years, the rate of inflation in the UK has been subdued as a result of stable labour costs, a good supply of relatively cheap energy, efficient global supply chains and technological advances.

Since the pandemic however, inflation has risen to a 10 year high (In October 2021 the Consumer Price Index reading was 4.2%) and it is forecast to continue rising. If you look at the Retail Price Index (RPI), the measure that includes mortgage payments, the reading was 6.0% in October.

Often the headline rate that is reported is the CPI figure but consumers are also impacted by the RPI as it affects the price of :

• Final salary pension payments

• Income from index-linked annuities

• Income from some index-linked bonds

• Train tickets

• Mobile phone tariffs

• Air passenger duty

• Car tax

• Tobacco duty

• Alcohol duty

• Interest on student loans

Many of these impact the measure of an individual household’s inflation.

The rate of inflation is closely watched by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) at the Bank of England (BOE) and historically, increases in the inflation rate often result in increases in the BOE Bank base rate.

At the November 4th meeting of the MPC, 90% of market participants expected the BOE base rate to be increased from 0.1% to 0.25%. This expectation resulted from hints given by MPC members in the run up to the meeting and specifically the message delivered by Governor Andrew Bailey who, on 17th October, at an online discussion with the G30 consultative group, stated that the BOE must act to curb the inflation that was resulting from higher energy prices.

When the MPC voted 7-2 not to increase rates at the meeting the excuse given was that the furlough scheme had just finished and therefore they wanted to see whether there would be a spike in unemployment.

Figures released on the 16th of November showed that the headline rate of unemployment fell by more than expected to 4.3% in September from 4.5% in August, and that total hours worked increased on the quarter with the relaxation of many (COVID-19) restrictions. Year on Year average hourly earnings however fell during the same period from 6.0% to 4.9%, and it may have been this last figure which prevented the MPC from acting.

After the release of these figures, market focus moved to the next MPC meeting on the 16th December, where the expectation of a base rate increase moved to 50%.

Using the UK base rate as a tool to reduce the inflation rate is a monetarist policy that, in normal market conditions, would have resulted in a base rate being much higher that it is currently.

When interest rates are low, consumers borrow more and spend more. The pent up spending that resulted from the lockdowns has fed into the UK economy which is now showing robust growth and this, combined with the low cost of borrowing, and poor returns from savings, has encouraged consumers to chase goods, many of which are seeing supply constraints.

Unless the MPC acts to try and reduce demand for goods and services by increasing interest rates, inflation will continue to increase. The higher prices currently being experienced in the economy will become the new ‘norm’ and are unlikely to fall, unless demand suddenly drops off.

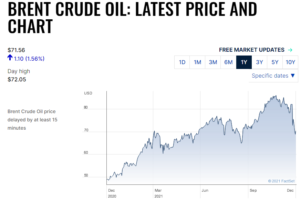

Energy prices have eased slightly in the last few weeks ( Brent Crude has fallen from a high of $85 to its current $71.50, but it was below $50 a barrel a year ago) and the release of reserves by the US and the decision to increase supply by OPEC+ has had little further impact on the price.

So the inflationary impact from higher energy prices is not abating, supply chains are still not functioning efficiently, labour costs are stable (and in certain areas such as hospitality are still increasing) and the deflationary pressures from technology are not currently sufficient to have a negative impact.

In short, none of the factors that have held down inflation for the last 10 years are evident. Whether the MPC raise rates at the 16th of December meeting or wait until the 4th of February meeting is just a matter of timing. UK rates are increasing, and this week, expectations of US rates following suit in 2022 have grown.

Higher interest rates are required to put the brakes on certain areas such as the escalating cost of housing. Emergency measures such as rock bottom interest rates are fine when conditions dictate, but they need to normalise when the emergency is over. COVID 19 will not be disappearing any time soon but the economy has recovered from the shock that it received. Central Banks need to act sooner rather than later to control inflation.

The only fly in that particular ointment is that the prime beneficiaries of higher inflation are those most heavily in debt (because inflation erodes the future value of that debt), a fact no doubt not being lost on the World’s central bank governors.

Jerry O’Keeffe. 03/12/2021